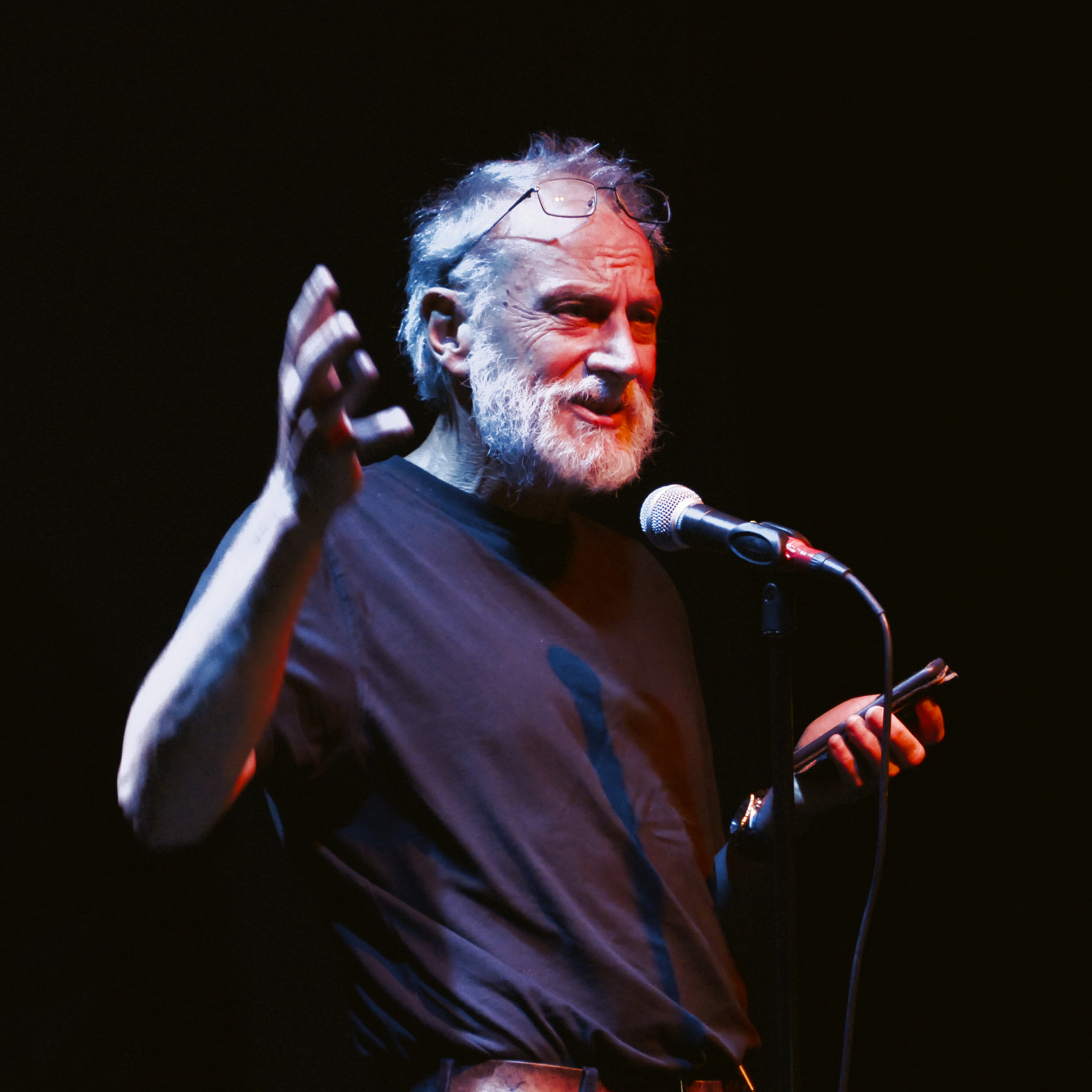

Ian Gibbins is a poet, video artist and electronic musician living in Adelaide, South Australia. His videos and audio work have been exhibited around the world in diverse festivals, galleries, installations, and public art programs. His poetry has been been widely published in-print and on-line, including four books, two in collaboration with artists, and several anthologies. In his former life, Ian was an internationally recognised neuroscientist and Professor of Anatomy.

For details of Ian’s creative work, visit www.iangibbins.com.au.

Ian Gibbins describes ‘Coming Through’ as: a sort of a road trip saga through rural Australia ending up in Sydney. This is one of my most popular performance pieces, and it is great fun to do live. There is a lot of local vernacular in it, so I hope it makes sense to a non-Aus speaker!!

By way of explanation, the ending of the poem is set in Sydney, with the truck going over the Sydney Harbour Bridge towards the North Shore, the affluent suburbs on the northern side of the Harbour. The Bridge is usually choked with traffic.The phrases “Coming through like a Massey-Ferguson tractor / Bondi tram / steam train / 10-ton truck …” were widely used not so long ago, although most people these days wouldn’t know much about the first three. Bondi trams were a feature of Sydney, but have not been around since the 1950s.“Fibro-cement” is a form of cheap building material often used for farm houses: it’s a sheet that contains asbestos. It’s usually referred to simply as “fibro”.“Sulphur-crested cockatoos” are large white parrots that are incredibly noisy, intelligent, and often very destructive of human-made items. They can live for up to 100 years, at least in captivity, and they learn to speak very well.“River red gums” are giant Eucalypts that grow along waterways in much of Australia. They can live for hundreds of years. Their timber is very dense and is coloured dark red. It is used for buildings, furniture, and once, for paving roads, especially those with tram lines (I grew up on a road with these).“Stripping off the top-soil…” One of the worst outcomes of drought that commonly afflict large areas of Australia, often for years at a time, is that strong winds blow away the dry top-soil, leaving very little for the farmers to use for sowing if and when the rains return.“The posters…” refers to a famous photograph of a sunbather by famed Australian photographer, Max Dupain.“All coal burnt… the stuttering gauge…” reflect the driver’s cabin of a steam engine.“Surfed South Coast reefs…” refers to the south coast of New South Wales which has some of the best surfing set-ups anywhere. During the 1970s, I often took my summer holidays in that area.“Commonwealth rail” refers to the government funded major railway lines such as the Indian-Pacific that crosses the continent from Pert to Sydney via Adelaide, and includes the longest straight stretch of railway in the world.

Coming Through

Sleep fell heavy upon him, memories

fragmented like fibro-cement ghosts,

like the farm house, abandoned, up bush.

So many names forgotten, hazy shadows

of kith, kin, a glimpse of forbearance,

an overwritten entry in the Family Bible.

What remains? What little is left?

Milk curdled in tea too hot for relief;

old sows surly with summer mudcake.

Sulphur-crested cockatoos sliced

gutta-percha from telephone wires,

called his bluff behind banks of river red gums.

Was this the final nightmare? The wind

stripping off the top-soil, the last inch

of story and hope and recompense?

He’d seen the posters – that body

buffed proud and shining and flecks

of perfectly polished Pacific Ocean.

He’d looked for sky and horizon and

the gradual build-up of cloud in the west,

a slow-brewed flash-flood to wash away

the metallic grit rusted on his skin,

the bone-char and sausage-grease

malingering, salt-dry, on his lips.

Pocket-holes frayed, finger-picked apart,

his pencil stub, indelible, oddly misplaced:

drawn blind, his darkening sense of danger.

A tremor, foreboding, unwelcome:

something surely about to break?

Nothing moved, nothing was said.

There are songs in this rhythm,

the insatiable drive to push on,

the indomitable reluctance

to stop, even when lines-end looms,

even when all towns and sidings

have been passed, all coal is burnt.

Tobacco, beer, comic strips, a crossword.

Did you place a bet? Has the alarm rung?

Could you read the stuttering gauge?

We cannot can play a worm-riddled piano

with too few keys, too many broken strings:

we can only whistle a love-lost tune.

Listen, listen: what do you hear?

Steel on steel. Steel on steel.

What more is there to concede?

High in the filigreed cab, he rides

the fractured asphalt, wipes his eyes,

scratches, scrapes, where once

he had hair, when once he worked

the land, surfed South Coast reefs,

crossed the country by Commonwealth rail,

sought romance and fortunes, imagined

simply there for the taking, ignored

the oscillations, the year on year

doubt on doubt, until now, at this point,

there is new forward momentum,

unbridled kinetic energy, until now,

when his warning, pure diesel distillate,

ignites: “Clear the Bridge, you lousy

North Shore bastards, I’m coming through…

like Massey-Ferguson tractor…

a Bondi tram…

a steam train…

like a bloody ten-ton truck!”